The UK and European Union moved a step closer to reaching a deal over their future relationship, with the bloc’s top officials confident Boris Johnson is willing to compromise and the prime minister saying the prospects for an accord are “very good.”

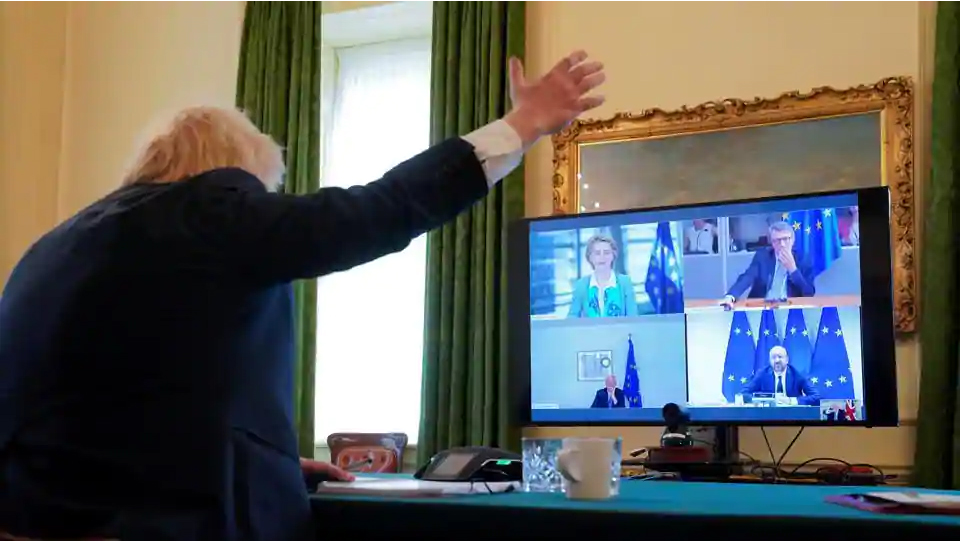

An hour-long video call on Monday between Johnson and the bloc’s leadership has injected fresh momentum into the deadlocked negotiations, according to people on both sides with knowledge of the conversation. The EU inferred from Johnson’s contributions that he is willing to soften his position and European officials told him they are ready to do the same.

“I don’t think we are actually that far apart — what we need to see now is a bit of oomph in the negotiations,” Johnson said in a pooled TV interview after the call. “The faster we can do this the better: we see no reason why you shouldn’t get that done in July.”

Johnson’s first direct intervention in the discussions since the UK left the bloc at the end of January marks the start of six weeks of intensive discussions to reach an agreement. After three months of trade talks ended in stalemate, both sides wanted to use Monday’s meeting to assess whether a deal is still attainable before Britain’s final split with the bloc at the end of the year.

In a sign that major obstacles remain, EU Council President Charles Michel warned the EU isn’t prepared to “buy a pig in a poke” in any rush to sign an agreement. In a Twitter post, he reiterated that the contentious requirement for a level competitive playing field between the two sides will be “essential” for any accord.

“We won’t just speed up,” Michel’s spokesman Barend Leyts said on Twitter. “We have to remain focused on content and consequences.”

Intensive Talks

Formal discussions will resume on June 29 in a more concentrated format than the previous series of talks every three weeks. The British government, which has ruled out extending the December deadline for negotiations, had been pushing for the discussions to be sped up.

In a sign that the EU is responding to that pressure, the two sides also committed to “if possible, finding an early understanding on the principles underlying any agreement” — implying that an outline of a deal could be reached before it is fleshed out.

While Johnson said he doesn’t want the talks “going on until the autumn, winter, as perhaps some in Brussels would like,” the UK last week agreed to a timetable that includes a negotiating round in mid-August. During the video call, Johnson didn’t set out a hard deadline, according to a person based in Brussels.

Privately, officials from Brussels and London say they are focusing on reaching an accord between mid-August and a summit of EU leaders scheduled for mid-October.

No Backtracking

Johnson told EU officials the UK is committed to the terms of the Brexit Political Declaration, which set out the broad parameters for the two sides’ future ties, a person familiar with the conversation said.

The declaration includes some of the EU’s key demands but the British government has questioned it since agreeing to it, saying it isn’t legally binding. Previously, the bloc’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, accused Johnson of backtracking on the commitments.

Since the negotiations started, both sides have struggled to make progress on a free-trade agreement and other aspects of their future relationship, such as fishing rights and security cooperation. The UK still rejects the EU’s call for a level playing field, which would bind Britain to some European rules in areas such as state aid and environmental law.

Those differences may not be irreconcilable, according an official with knowledge of the talks — but neither side has yet broken with its key red lines. In particular, the UK is sticking to its refusal to allow the European Court of Justice to be involved in settling any disputes between the two sides, a key demand of the EU.

Johnson’s call with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, Michel and other EU officials, came after he formally ruled out extending the negotiating period beyond the end of the year. Failure to get a deal by then would see Britain and the EU trading on World Trade Organization terms, meaning tariffs and quotas would be imposed at a time when the region’s economy is still reeling from the coronavirus.